India’s arduous march from easy to hard money

As RBI takes a hard money turn, companies, consumers, banks and governments will have to shift to new ways. Will we be able to balance between inflation and growth or are we headed towards stagflation?

As RBI takes a hard money turn, companies, consumers, banks and governments will have to shift to new ways. Will we be able to balance between inflation and growth or are we headed towards stagflation?

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) allowed cheap money to continue for long. It didn’t matter that India was having inflation that was hurting, savings in banks were effectively earning negative, and the tales of common people living with less were growing.

The decision not to touch the interest rate minefield was taken with the sole motive that growth would somehow kick-start and gather speed even as we battled against the coronavirus pandemic, lockdowns and supply chain disruptions.

The easy money period helped certain sectors of the economy rebound, companies deleveraged to bring down their debt, fintechs adjusted into the system, and the number of unicorns grew. The IPO (initial public offering) market was alive, with some individuals even sourcing cheap debt to invest in the fresh issues.

The stock market remained buoyant during this phase as bank deposit rates crashed to a new low. Mutual funds as investment vehicles grew with SIP (systematic investment plan) inflows rising to its highest ever, from Rs 11,447.70 crore in February to Rs 12,327.91 crore in March. The assets under management (AUM) from SIPs grew to Rs 5.76 lakh crore, up from Rs 5.49 lakh crore in February.

As the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) reeled under Covid stress, the RBI provided liquidity support of Rs 17 trillion in the past two years, out of which Rs 12 trillion was utilised. Restructuring schemes were introduced, providing moratorium to individual borrowers and small-and-medium businesses.

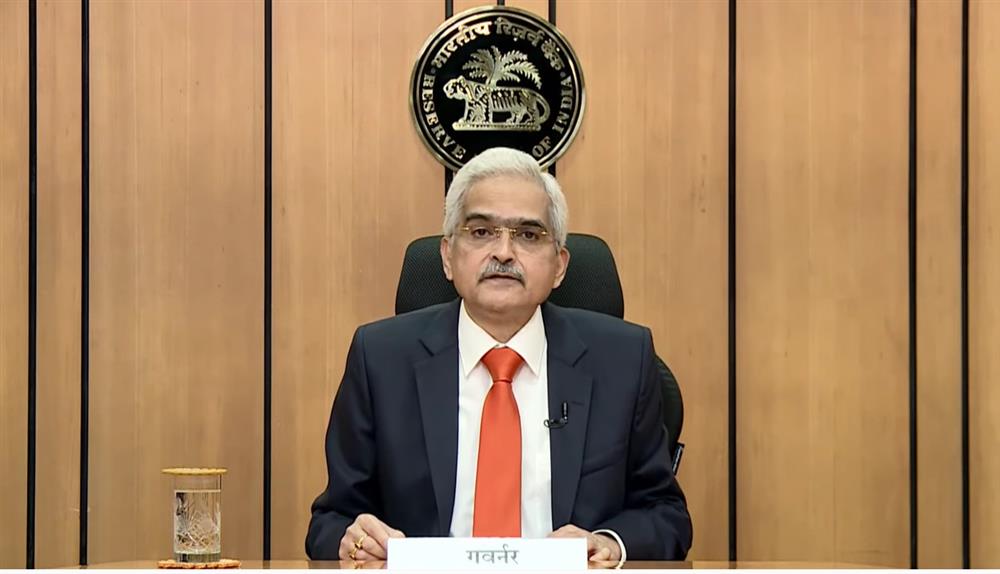

RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das, at an event organised this March by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), said that the central bank had remained supportive of growth for the past two years and resisted all temptations to move away from the accommodative stance because “we could see that inflation would moderate and it did moderate”.

While the RBI provided the crutches to support growth, there was a parallel shadow growing in the economy. Jobs were getting lost. Wages were cut. Consumer demand was weak. Inflation was rising. Living standards were squeezed.

Nabi Swain left her small patch of agricultural land in Niali, a village in Cuttack district, to work as a domestic help in Bhubaneswar as she was unable to fund her son’s education in an engineering college. Her husband had lost his job in a construction company and remained in the village to do farming. Her elder daughter, a graduate, found a job in a pharma distribution company. They rented an outhouse in the capital city of Odisha and cut down on food expenses with the hope that the son would land up with a job after his engineering diploma and take care of the family’s financial needs.

The job data, however, has not been very encouraging. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), unemployment rate rose to 7.83% in April from 7.60% in March. The urban unemployment rate increased to 9.22% in April from 8.28% in the previous month. The comparable figure in rural India was an unemployment rate of 7.18%, marginally better than 7.29% recorded in March.

The message from the RBI all this while was crystal clear: growth was the bigger demon and, if addressed, other problems would get sorted out.

India’s GDP did limp back and a slow recovery trend was visible, after shrinking by 6.6% in 2020-21 due to the Covid-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdowns imposed by the government. For the financial year 2021-22, India’s GDP is estimated to grow at 8.9% with recovery being a little broader but still uneven.

However, even with the government and the RBI throwing their weight behind growth, corporate investments have stayed muted. Turning negative in mid-2021, real credit growth is just around 2%.

There is a structural problem that crept in even before Covid made its arrival. India’s growth rate was slowing due to weak consumer demand. In the pre-Covid year of 2019-20, GDP growth dived to just 3.7% compared to the preceding two decades when the average was over 7%.

Some economists termed this as a slippage into the middle-income trap, which means a country’s growth starts faltering at lower-middle-income levels, with per capita income between $1,000 and $3,800. What is required in such cases is course correction.

Caught in a complex web, the solution to growth could not be found just in a monetary policy. And while growth took its own time to find its running feet, inflation was rearing its ugly head. India’s inflation wolf grew in size to eight-year high of 7.79% in April, breaching the RBI’s upper tolerance limit of 6% for the fourth month in a row. Led by food items and fuel prices, consumer price index (CPI) inflation was getting broad-based.

The Russia-Ukraine war, which started on 24 February, upset everything as it led to supply-chain disruptions, soaring oil prices, global slowdown and high inflation across the world. India had to also bear the brunt of rise in edible oil prices. With Russia and Ukraine being breadbaskets for the world, UN chief Antonio Guterres warned that the conflict would cause a “hurricane of hunger and a meltdown of the global food system”.

The RBI, however, did not change its pro-growth stance and still felt that it could tame inflation. At the CII event on 21 March, Das said that the current crisis in Europe could have an impact on inflation in India but the possibility of the prolonged breach of the laid down tolerance band is remote.

By the time of announcing the monetary policy in April, RBI’s discomfort with the inflation levels was growing but it kept the repo rate unchanged at 4%. The inflation forecast was revised upwards to 5.7% in FY23, from its earlier guidance of 4.5%. The GDP growth estimate was revised downwards to 7.2% from 7.8% before.

There was a realisation that the coronavirus pandemic was having a lasting impact on India’s economy. Towards the end of April, RBI said that India would overcome Covid-19 losses in 2034-35. This took into account the actual growth rate of (-) 6.6% for 2020-21, 8.9% for 2021-22 and assumed growth rate of 7.2% for 2022-23 and 7.5% beyond that.

The RBI’s worry point obviously was growth. As data would indicate, India’s inflation is not demand-led. In 2020-21, per capita consumption expenditure regressed to its level of three years ago. According to the CMIE data, the per capita real private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) measured Rs 55,783 during the year, levelling with its value of Rs 55,789 in 2017-18. This picked up in 2021-22 as Covid-led lockdowns eased, but not to any significant level.

The inflation in India is supply-led and has coincided with rise in commodity prices, excess liquidity and shrinkage of incomes in poor and lower middle-class families. Consumer demand is sluggish and if any segment has seen a significant rise, it is among the upper-income spenders. In the US and some European countries, inflation is demand-led in the midst of supply-chain issues, wage rises and stimulus packages.

The RBI took time to firmly believe that inflation would require a targeted monetary policy response. Until it raised the repo rate by 40 basis points to 4.40% in an unscheduled announcement on 4 May and said the cash reserve ratio (CRR) would rise 50 basis points to 4.50% from 21 May, the central bank felt that inflation was transitory and would get corrected once the supply-side situation improved, both on the food front and on energy prices.

The Reserve Bank also gathered confidence from the fact that the country’s foreign exchange reserves had gone up by almost $270 billion in the last three years. It had even hit a record high of $642.45 billion in September 2021. At the CII event this March, Das said India is comfortably placed with any challenges emanating from the geopolitical crisis with its high forex reserves.

The unending war in Ukraine, however, upset all balances. With the market forecasting a rate hike of 50 basis points by the US Federal Reserve, the RBI also did not want to be seen as being behind the curve. The RBI, however, did not put markets on notice that it would be initiating a rate hike cycle. Das made the surprise announcement in the afternoon of 4 May ahead of the Fed rate hike, prompting panic selling in the bond and equity markets.

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman admitted the timing could have been a surprise to many, though the rate hike was not. “It is the timing which came as a surprise to many, but the act people thought should have been done anyway—to what extent could have varied,” she said recently at the Economic Times Awards for Corporate excellence.

A few days after the Federal Reserve hiked the rate, the rupee sank on Monday to close at a record low of 77.46 against the US dollar. It further sank to an all-time low of 77.63. Foreign institutional investors (FIIs), seen to be migrating from the Indian equity market, are set to increase their outflows with net sales in 2022 being Rs 1.3 lakh crore so far. Besides impacting stock prices, this is going to put the Indian currency under further pressure.

“Given the current global circumstances, the Indian rupee will continue to find the going tough for the rest of the year. It could edge closer to the 79 mark in the next couple of months before settling down in the 76-77 bracket,” said Ritesh Bhansali, vice president at Mecklai Financial.

A falling rupee can push up inflation. With India importing 80% of its crude requirement, rising oil prices due to the ongoing war in Ukraine will continue to put the heat on inflation. The RBI, though, has the resources to shield the rupee by using its forex reserves, which have taken a dip in the last few months to fall below the $600 billion mark in late April but is still high.

The RBI now has no option but to take a hard money turn. Fearing FII outflows and high inflation, the RBI has kicked off its rate hike cycle. Central banks in many countries, including the Bank of England, have also begun raising rates to counter high inflation. The US Federal Reserve has raised its benchmark interest rate by 0.5% and indicated that there would be further hike cycles.

Clearly, the era of ultra-low interest rates is over. Russia’s war in Ukraine, the tightening of the job market, the resurgence of inflation and the intensity of geopolitical hostilities will have a bearing on how future economies and governments are shaped. Companies, consumers, banks and governments will have to shift to new operational ways as they enter into a phase of high interest rates.

Governments around the world will have to make the adjustments. The Narendra Modi-led government’s privatisation drive came during the low-rate phase. In a high-rate cycle, this may face challenges. The government-run food subsidy scheme and the borrowing programme will also become costlier.

Modi gained from a long spell of low oil prices. But a lot will change now with oil prices expected to stay above $100 a barrel. These external forces will challenge the government to manage current account deficit, balance of payments and fiscal deficit, along with the social welfare schemes.

As interest rates harden, there is a change that companies will now have to plan for. Reliance Industries and the Adani group, India’s two leading business houses, used the low-rate environment to grow even in the Covid period. Several other companies trimmed their debt and cut down on costs to go through a period that saw sales down but profits up. When they return to their investment cycles as growth picks up, they will have to source pricier loans.

Banks, which are funded by deposits, always prefer an environment where they can price their loans higher. For a long time, they had to depend on treasury as a substantial income contributor as interest rates stayed bottom low and there was no demand for corporate credit. Low deposit rates also meant money was moving out from banks to other investment avenues, including the equity market. On the asset side, low credit growth meant there was little impact in the banking sector during the easy money period.

“It was a peculiar situation when loan rates were below the sovereign rate. Now we can have proper pricing of rates,” SBI managing director Ashwini Kumar Tewari told indianbankingnews.com.

Banks will be in competition to grow their deposits portfolio. “On the deposit front, the banking sector had seen some element of migration as rates were low and considering the rate of inflation, there was a negative carry. We will see deposit growth as rates go up,” Tewari added.

Punjab National Bank managing director and CEO Atul Kumar Goel believes the margin advantage banks have due to the lending rate rise will get squared off. “As we moved to a higher interest rate regime, we may have an advantage of higher margins for one or two quarters. Only those loans linked to the external benchmark lending rate or the repo will get repriced immediately. But the deposits will get repriced as and when it matures, along with the loan rates depending on the reset date. This will net off the margin advantage that we have,” he said.

For consumers, borrowing costs will go up. The place where this could have an effect is housing loans, an area which has seen significant growth in recent months. Auto and personal loans will also see similar rate rises. Retail credit could slow down in a rising rate scenario, unless growth in the economy offsets that.

Tewari believes that housing can weather rising rates, particularly when the loans are already at such a low level. “For banks, mortgage loans will continue to see robust grow. So will gold and personal loans. Auto is facing problems on the supply side, but this will get sorted out. With retail loan pricing having taken such a dip, a rise in interest rates from here on shouldn’t be a detriment to credit offtake,” said Tewari.

A lot, though, will depend on how long the war lasts, how intense is the inflation and how immune growth is to these adverse conditions.

The rise in bond yields could pose a problem. “What is worrisome is if government bond yields rise sharply, it may try and cut back on capital expenditure. This will be growth negative in many ways,” said Abheek Barua, chief economist at HDFC Bank.

If the economy stagnates and the inflation dragon does not come under control, there is fear that we could be heading towards stagflation. But Tewari rules this out as being too far-fetched.

“Recovery has been improving and growth is coming back. Certain sectors like steel and infrastructure are going to see investments. Tata Steel, for instance, has planned capital expenditure of Rs 12,000 crore for 2022-23. Even contact-intensive sectors will do better if Covid doesn’t return. There may be some impact of higher rates on MSMEs but more important for them is liquidity and timely availability of credit,” he said.

While setting out to tame inflation through a series of rate hikes during the course of the year, the RBI will have to be careful that it does not hit the brakes too hard on growth. The economy needs to generate employment, uplift livelihoods and restore the health of small businesses.